The idealized nude is a trope in Western art, with works like Michaelangelo’s David or Titan’s Venus of Urbino hardly raising eyebrows these days. But what about those works whose subjects slid right past first base (and sometimes even second and third)? These ten head-scratching artworks, excerpted from Phaidon’s new The Art of the Erotic are salacious and outrageous, sure to even make the most open-minded Casanova blush. Take a peek, and if you’re at work, make sure your boss isn’t standing over your shoulder!

Anonymous (Moche, Santa Valley)

Handle Spout Vessel in the Form of a Female and Skeletal Figure in an Erotic Embrace

100 B.C—500 A.D.

The Moche civilization dominated the arid north coast of Peru from around the first to the eighth century AD. Its peoples harnessed the waters of the Andes to create a sophisticated culture with a highly stratified urban society centered on ceremonial pyramid complexes called huacas. Their material culture includes exquisitely crafted textiles, ornamental objects in gold and semi-precious stones, wall paintings, tattooed mummies, and ceramics. The ceramics preserve images of war and daily activities such as weaving, and a group of at least 500 vessels carries explicitly sexual images in the form of three-dimensional sculptures on top of or as part of the pot. The vessels are always functional, with a hollow body to hold liquids and a pouring spout, often in the form of a phallus. Sodomy, fellatio and masturbation are most frequently represented; cunnilingus is never found, and examples of penile penetration of the vagina are so rare as to be virtually absent. The most common position is anal sex, but in most of these cases the couple is heterosexual, not homosexual, their genitalia carefully detailed. Another common image includes a male skeleton who masturbates or is masturbated by a woman.

The meaning of these sexual sculptures is debated, and suggestions have ranged from their being educational images providing instruction on contraception, to examples of Moche moralizing or humor, to the portrayal of ceremonial and religious rites. They are mostly without archaeological context, but recent systematic archaeological excavation suggests that they were elite grave gifts.

This vessel comprises a fully fleshed woman masturbating a male skeleton. It has been proposed that the message may be that of continuity between the living and the dead. In the pre-Columbian languages of the Andes, the concepts of “ancestor”, “lineage” and “penis” are linguistically linked. The woman’s hand rubbing the skeleton’s penis may have been seen as activating the ancestral potency of a dead ancestor and, via her living sexual activity, transmitting that power to the lineage’s descendants. The vessel should be understood in the context of social inequality: for the powerful and wealthy, the point of reproduction was not simply the bearing of babies, but the creation of heirs who would continue the lineage and control the political and economic resources amassed by their ancestors. The presence of these “sex pots” in elite tombs, and the representation on them of skeletal figures, thus places sex in the house of the dead and the lineage of the ancestors. Based on anthropological comparisons with Amazonian and other South American cultures, bodily fluids may have been understood by the Moche as tangible links to the ancestors, at the same time acting as nurturing fluids passed from man to woman as seminal fluid, and from woman to infant as breast milk.

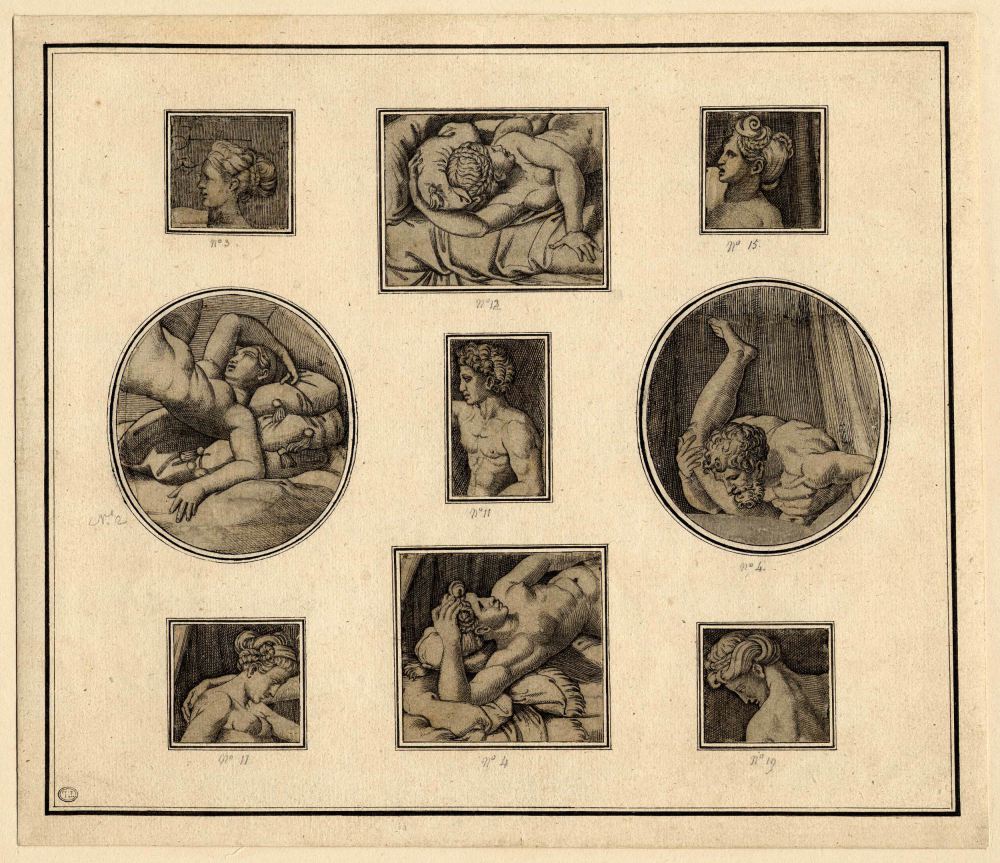

Marcantonio Raimondi, after Giulio Romano

I Modi (The Positions)

c. 1510-20

These fragments of larger, more graphic images tantalize us with their suggestions of what has been cut out, for they are all that remains of an explicit set of sexual instructions known as I Modi (The Positions), suppressed for centuries by the Catholic Church. Mounted on a sheet are the remains of nine separate engravings printed from copper plates: four show female heads in profile, while three depict the naked upper bodies of women in positions that hint at intercourse. Two nude males seen from the torso up suggest similar activity. The fragments have been cut carefully to avoid any explicit details, forcing us to guess at their original graphic content, but ultimately ensuring their survival from censure by the Vatican.

The original edition of I Modi was devised by the Italian engraver Marcantonio Raimondi, who based his designs on sixteen images of sexual positions reputedly drawn by Giulio Romano, court artist to the duchy of Mantua. Romano also designed and decorated a new pleasure palace, Palazzo Te, filled with a number of erotic frescos, for his patron Federico II Gonzaga on the outskirts of the city. He is also believed to have painted for the same ruler the enigmatic Love Scene (1524–5). Romano had trained under the Renaissance master Raphael, many of whose more widely known works Raimondi also engraved.

According to the satirist Pietro Aretino, Raimondi was immediately arrested upon publication of I Modi in 1524 under the orders of Pope Clement VII, who demanded that all copies be destroyed. Romano evaded any punitive measures, seemingly it was the widespread dissemination of the images afforded by Raimondi’s engravings which drew the ire of the Church. Aretino himself published an edition in 1527, this time accompanied by erotic sonnets he had written which described each scene. This edition too was widely suppressed though the sonnets remain known to us from a sixteenth-century book illustrated with clumsy woodcuts. The provenance of these nine fragments is unclear though it has been argued that they are likely to be early copies of Raimondi’s original engravings, generated from a replacement set perhaps by the engraver Agostino Veneziano.

Despite facing religious censure, I Modi found illicit interest across Europe and continued to be revived whether in the form of direct copying, as in the set of sixteenth-century woodcuts, or by exerting influence as in the erotic engravings of Agostino Carracci (see below). An eighteenth-century text entitled L’Arétin d’Augustin Carrache, ou Recueil de Postures érotiques, d’après les Gravures à l’eau-forte par cet Artiste célèbre continued the tradition of Raimondi, also borrowing the names of Aretino and Carracci, with its catalogue of sexual positions to which it lends a veneer of respectability by giving its subjects names drawn from classical mythology.

Despite strictures from religious authorities, people down the years kept these images safe, aware that what we imagine can arouse us at least as much as the readily apparent.

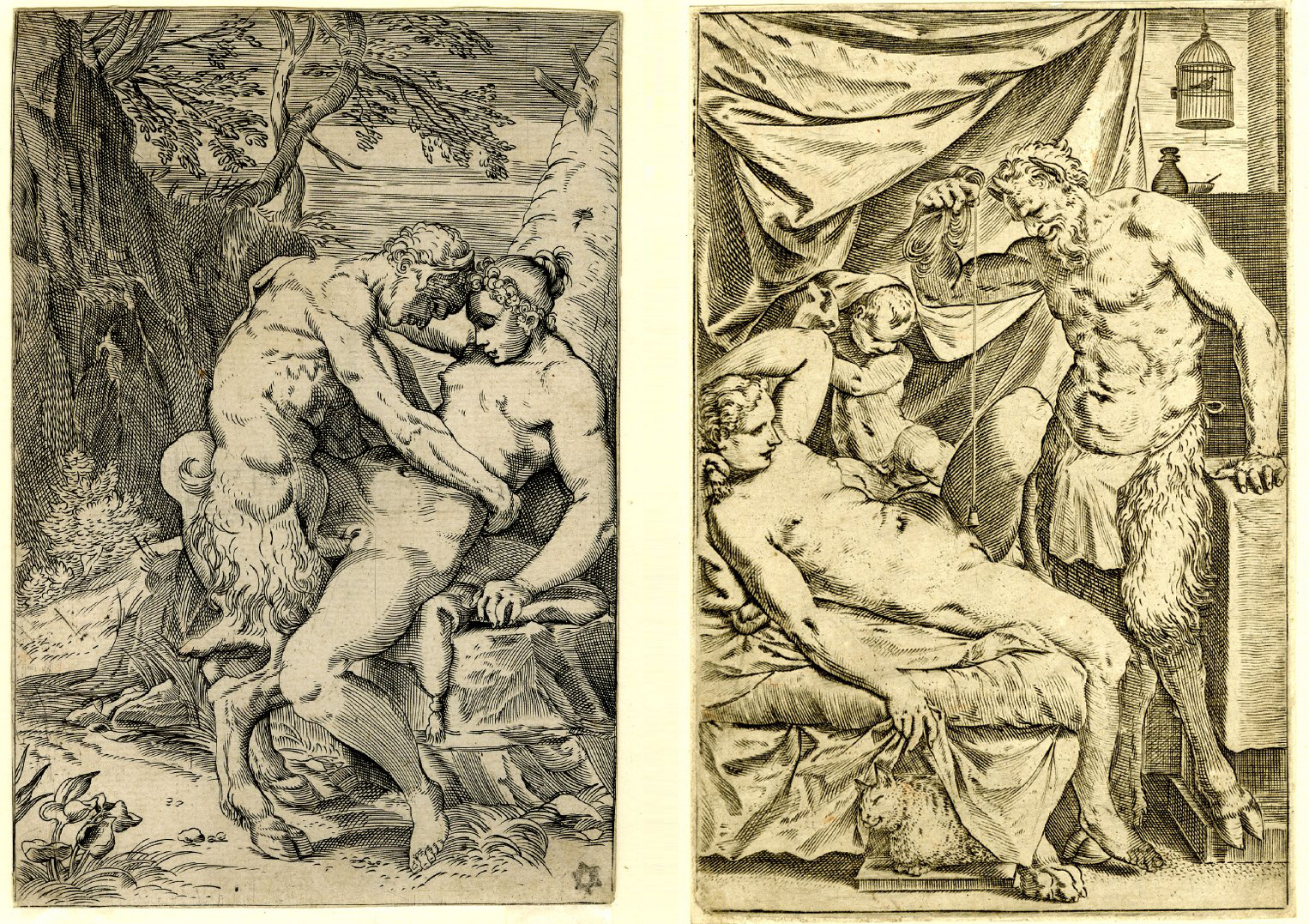

Agostino Carracci

Lascivie

1585–1600

The erotic prints in this set are among very few such works to have survived from the sixteenth century, during which a huge expansion in printing technology allowed a wider array of collectors than ever before to pursue their specialist interests. Many such editions would have been suppressed during moralizing purges, among them the infamous I Modi (The Positions) by Marcantonio Raimondi. Produced by the acclaimed engraver Agostino Carracci, the Lascivie are less explicit than Raimondi’s works, and include a wider range of biblical and mythological subjects, of which these two are examples. One engraving shows the Three Graces standing in forward-facing, backwards and three-quarter poses; the rest follow a theme popular in the collection: satyrs and nymphs. In one we see a goat-like creature standing to make love to a nymph seated on a rock, while another engraving shows a male figure gazing at a nymph sleeping under drapery similar to that employed by Nicolas Poussin in his later work Jupiter and Antiope. Finally, in the peculiar Satyr Mason, the eponymous subject in an apron holds a plumb line over the female’s crotch. She shares her bed with a child; the composition also includes a cat on the floor and a birdcage in the background.

Carracci was one of three brothers, including the more famous painter Annibale, who did much to pioneer the seventeenth-century Baroque’s propulsive and detailed style of painting. Agostino himself was recognized as one of Italy’s finest engravers, thanks to the fine prints he made of paintings by contemporary masters, among them Paolo Veronese, Antonio Allegri da Correggio and Tintoretto. This particular series, though, is of his own design and shows him to be a talented artist in his own right, able to re-create classical themes and tell stories in a clear, concise manner. While the Lascivie are more complete than I Modi, they still come to us in a fragmented manner, meaning that it is unclear whether they were created as a series or collated only later. Writers from the seventeenth century have described a book of such prints, although the number of plates mentioned has varied from the teens to the twenties. The two outdoor satyr scenes are most closely related, linked by both subjects and the woodland landscape, yet the picture of the copulating pair appears to have been done earlier, if we can judge by the uniform thickness of Carracci’s lines. As the artist progressed, he developed softer, more rounded forms. This suggests that the artist worked on what became the Lascivie over a period of time, and that the project evolved from one-off prints into an open-ended group with a common format.

Related Works

Henry Fuseli

Drawing of an Erotic Scene with Three Women and One Man

1809

While many concupiscent images relocate their sensuality on to the handling of paint, or displaceit into surrogate objects within the picture – foamy seas, cascading hair, writhing putti – this drawing by Henry Fuseli is firmly anchored within the realm of nineteenth-century erotica. In this pencil and watercolor sketch, three women couple with a prostrate man, his head hidden between the thighs of the woman on the right. The four bodies form a pyramid; the figure at the apex lowers herself on to the erection of their common lover, while the third figure assists by holding his penis. The women’s clearly evident pubic hair and brazen sexual appetites suggest that they are prostitutes. Their elaborate hairdos corroborate that through a link to earlier works in Fuseli’s oeuvre, such as Two Courtesanswith Fantastic Hairstyles and Hats (c.1796) and The Debutante (1807), although those two works are not themselves sexually explicit.

Fuseli, born Johan Heinrich Füssli, was a Swiss painter who settled in England following an extended sojourn to Italy, where he changed his name from the more Germanic Johann Heinrich Füssli. Drawn to subjects that ranged from the supernatural to the works of Shakespeare, Fuseli cemented his reputation with a painting of a prostrate woman attended by a wild-eyed mare and a grotesque little demon identified as an incubus. This painting, entitled The Nightmare (1781), garnered both critical acclaim and opprobrium when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1782; although it did not diminish the painting’s popularity, the suggestion that the young woman was in the midst of an erotic dream or in a post-orgasmic state was scandalous.

The type of eroticism seen in The Nightmare, however, while overt, is decidedly different from that of the watercolor and pencil study shown here, which has more in common with the sexually explicit drawings Fuseli made while in Rome. Images such as the Symplegma on an Altar before a Herm of Priapus or the Symplegma of a Man with Two Women (both c.1770–8), in which the man’s prone form is very similar to that of the above watercolor, show explicit coupling and, like the watercolor, have an indeterminate purpose. Were they objects of exchange among Fuseli’s peers, or were they for private consumption, to be used for the purpose of self-pleasure? Fuseli inscribed the sketch with a line from Aeschylus’s tragedy Prometheus Bound –”Thus fatal to my foes be love”–perhaps hinting at the latent dangers of sexual love.

Katsushika Hokusai

Tako to ama 蛸と海女 (Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife) from Kinoe no Komatsu

1814

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This is perhaps the most bewitching shunga (erotic) image of all time, and it is certainly one that has fascinated audiences for centuries. It was painted by the great artist Katsushika Hokusai, and depicts a diving woman who has been dragged down to the depths of the ocean, where a brilliantly colored octopus is taking its pleasure of her. As all eight legs caress and fondle her, its great mouth performs cunnilingus on the woman, who has given herself completely to the bulbous black-eyed monster.

A smaller octopus kisses her mouth, and her arched back and the way she grips the octopus’s tentacles reveal her heightened sexual arousal, which is echoed in the sighs and exclamations in the text that surrounds the scene.

Hokusai was not the first artist to conceive of this exotic fantasy. Several earlier shunga artists depicted diving women being pleasured by octopuses, including Katsukawa Shunchō and Suzuki Harunobu. Yet Hokusai’s is the most alluring and certainly the most famous in the West, thanks to a biography and catalogue of the artist by Edmond de Goncourt, published in 1896.

Most of Hokusai’s shunga pictures were made between 1814 and 1823, when the artist was in his late fifties and sixties, and it is thought that he made some eighteen books in total. This sexually explicit image comes from his third book, Pining for Love, which he made in 1814. The book begins with a picture of a beautiful woman, and each scene thereafter depicts her in various states of passionate arousal with a lover, until the final picture focuses on a close-up of her genitals.

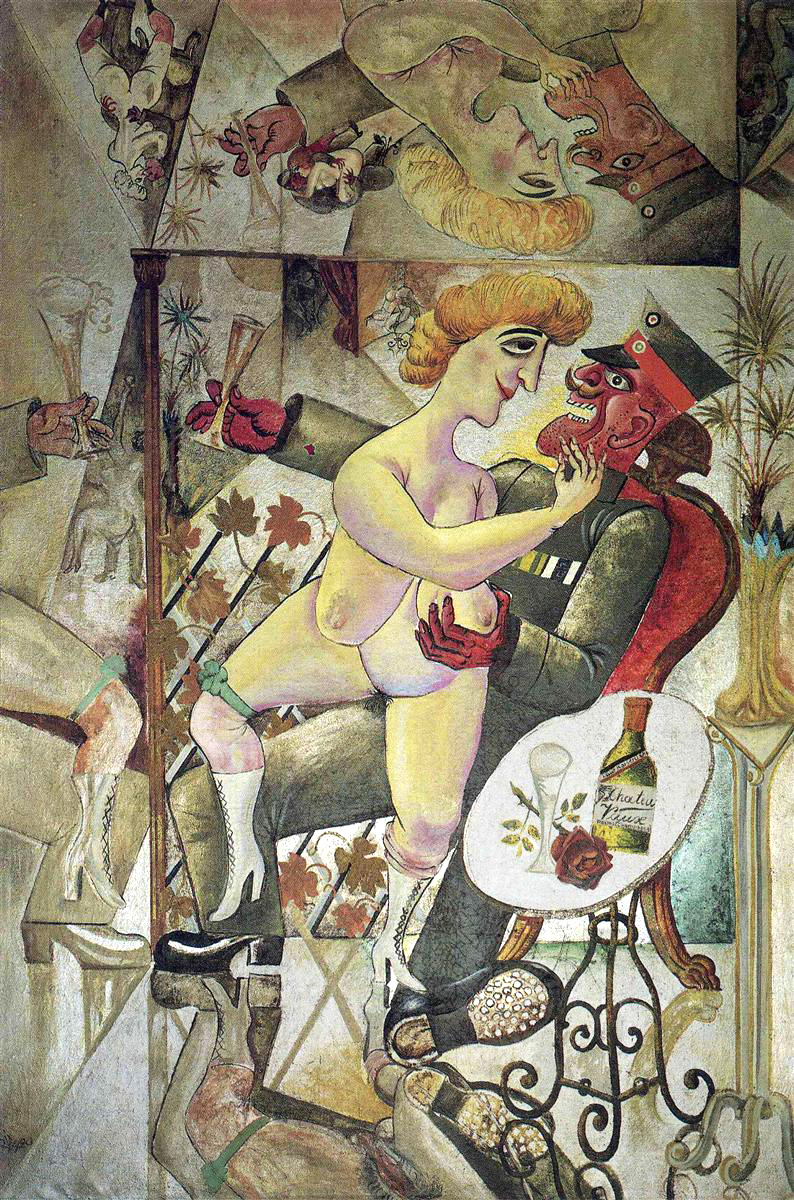

Otto Dix

Memory of the Mirrored Halls of Brussels

1920

This picture was meant to shock. It was painted by the avant-garde German artist Otto Dix in 1920, and it marks a significant moment in the artist’s development as he began to abandon the eclecticism of Cubism and Dadaism in favor of a fierce Critical Realism. The painting depicts a crimson-faced general, flushed with red wine, groping the swollen breast of a fleshy, naked prostitute. The multiple mirrors replicate the scene from every angle, so that the woman’s crudely painted vagina can be seen in reflection on the brothel floor, while her buttocks frame the scenes in the right-and left-hand sides of the picture.

In common with many of Germany’s avant-garde artists, Dix’s social consciousness was aroused when confronted with the sordid realities of the Weimar Republic. Having served as a soldier in the First World War, he yearned for a better society in which men could transcend their social levels. His moral outrage at the grotesque and decadent decay of post-war Europe became the defining subject of his paintings, and he honed in on the prostitutes, pimps, profiteers and beggars who had emerged in the intervening years. His anger at the victimization of the war wounded, who had been left half-starved and unable to support themselves, was represented unsparingly, contrasting the suffering of the unfortunate with the monstrous greed of the rich.

In Brussels, where this painting is set, the sex industry had become rife during the war because soldiers were allowed to carouse for a week or two before resuming their fanatical slaughter on the front line. The subject matter is meant to be offensive, and indeed in 1923 it brought Dix to the German courts, where he was tried and acquitted for obscenity. It is a hedonistic vision of carnal lust, rendered gratuitously with a raw erotic power that never fails to excite and shock.

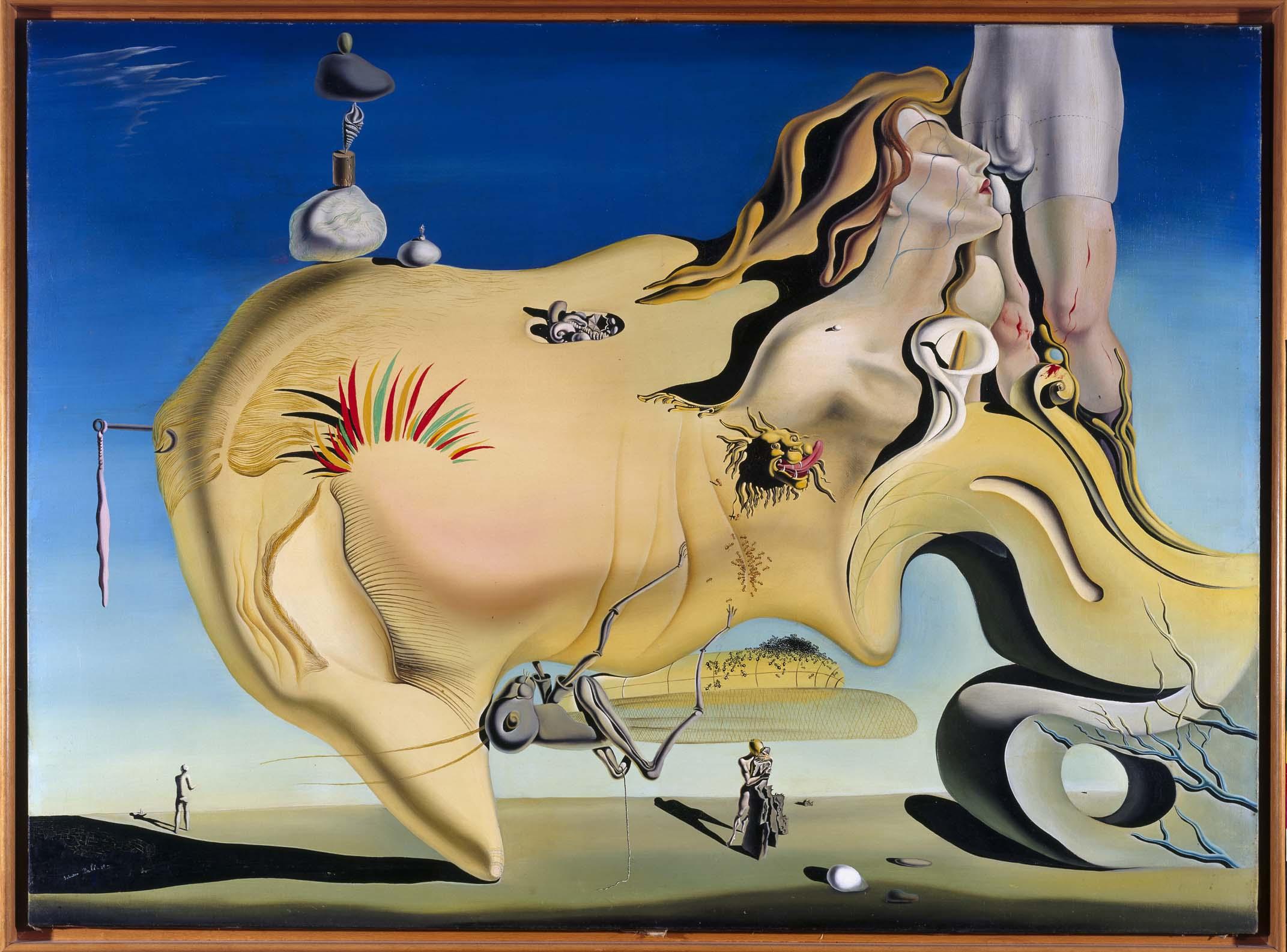

Salvador Dalí

The Great Masturbator

1929

The Spanish Surrealist Salvador Dali described The Great Masturbator as his self-portrait, as an “expression of my heterosexual anxiety”, and said that “masturbation at the time was the core of eroticism.” Dalí was very open in interviews and in his three autobiographies about his anxiety about genital intercourse as well as his preference for autoeroticism. A “panic fear of venereal diseases” began at a young age, when he saw medical photographs of the devastation they wreak in a textbook left by his father on the family piano. Dalí was also anxious about the size of his penis, which he felt was small compared to those of his classmates, and an account of an intimidatingly large member in a pornographic novel he had read led to his chronic impotence. He was still a virgin at the age of twenty-five (the time of this painting), when he met Gala Éluard, whom he married five years later. In fact, one chapter in a Dalí autobiography was entitled, “How to Become Erotic while Remaining Chaste”; but the artist said that his wife – who was ten years his senior – did help him to refine his masturbatory technique.

The giant central form in this painting is one of Dalí’s signature, flaccid self-portraits, seen most famously in the foreground of The Persistence of Memory (1931), where it is surrounded by melting clocks. In The Great Masturbator, Dalí’s head faces downwards, the tip of his nose touching the earth. To the left one can discern an eyelid and lashes (the fur-lined vertical slit suggests female labia), an eyebrow, a furrowed forehead and parted hair. Dalí is asleep, and the painting illustrates his dream. A woman—whose chastity is indicated by the white lily, a symbol in Western painting of the Virgin Mary—emerges from his head and luxuriates in her olfactory encounter with the artist’s genitals, hidden beneath his undershorts. Mounting Dalí’s face is a grasshopper with a mound of devouring ants in the place where we would expect its pubis if we were to anthropomorphize it. The image of devouring ants appeared the same year in the film Un Chien Andalou, directed by Dalí and the Surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel. In one scene, a hole appears in a man’s hand—the instrument of masturbation—after he fights with a woman. Ants swarm into and out of the hole, symbolizing the danger of a vagina dentata. Dalí had an intense fear of female genitalia, but in the fantasy illustrated in The Great Masturbator, he can avoid the woman’s sex and satisfy her sexually without either of them ever getting naked.

Dalí’s exploration of sexual and dream content is characteristic of the Surrealist movement, which he joined the same year as making this painting. The Surrealists translated Freudian ideas on dream interpretation, the unconscious, and the sexual and aggressive drives into literature and art. Bourgeois society tends to repress the biological drives, a process the Surrealists sought to undo through their shocking art.

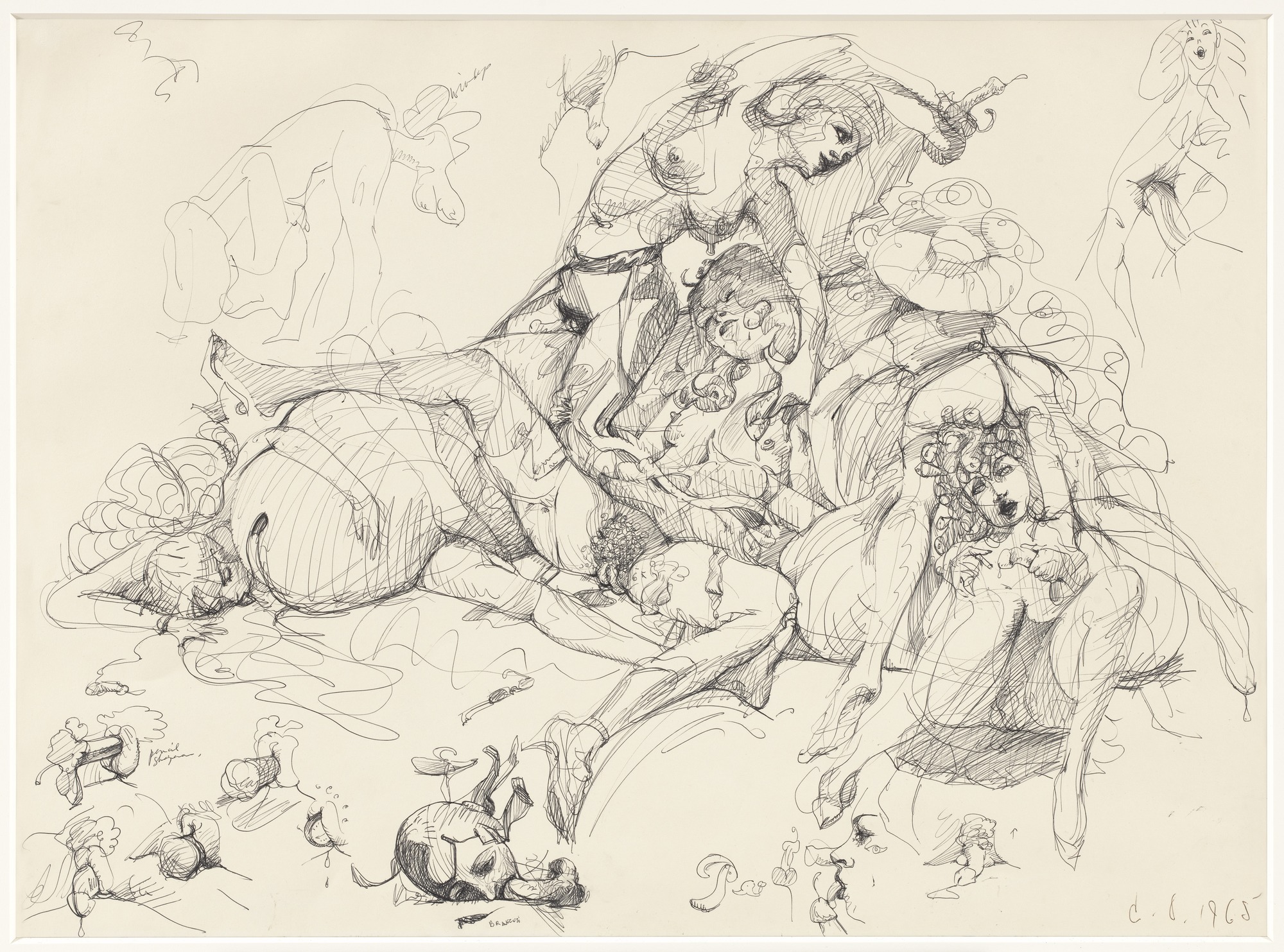

Claes Oldenburg

Clinical Study, towards a Heroic-Erotic Monument in the Academic/Comics Style

1965

Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

This drawing was made in 1965 by the American Pop artist Claes Oldenburg as a raunchy retort to bourgeois pretension. Drawn in ballpoint pen to give sharp definition to the characters and to mimic a cartoon, it depicts a group of slovenly female figures straddling a giant, flaccid penis. Their burlesque clothes evoke the heady era of fin-de-siècle Paris, with their Folies Bergère petticoats hitched above their waists as they press their buttocks up against the giant scrotum, which is obscured by their cavorting bodies.

Oldenburg is best known for monolithic sculptures in which he scales up everyday mass-produced items—such as a lipstick, a vacuum cleaner or a hacksaw—to vast proportions. Less well known are his exquisite erotic drawings, which he began making in the early 1960s, inspired by the classical Romanticism of nineteenth-century Europe.

Clinical Study, towards a Heroic-Erotic Monument in the Academic/Comics Style came about after the artist visited Washington, DC, while working on his early performance piece Stars (1963; also known as Cleaners). The city is dominated by neo-classical statues of politicians, which the young artist saw as homages to sex and power. He decided, with a cockeyed enthusiasm, to flatten all that pomposity by proposing a new type of monument, and these delectable cartoonish females are an early prototype. In fact, the drawing reflects much of the underlying content of Oldenburg’s subsequent sculptural propositions, in which he undermined historical tradition by proposing witty, monstrous alternatives.

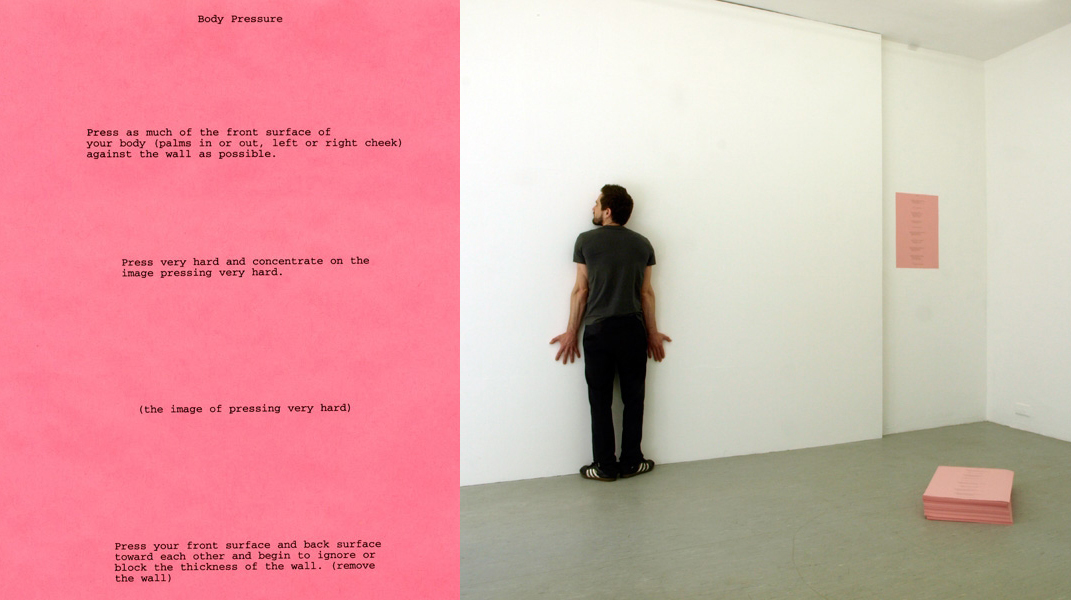

Bruce Nauman

Body Pressure

1974

Images courtesy of Sperone Westwater; photograph by Jacob Birken

The conceptual artwork Body Pressure consists of a list of written instructions from the artist, Bruce Nauman and comes to fruition as an artwork when these are performed. The words are usually displayed on a gallery wall with additional sheets of paper available, which viewers are encouraged to take away with them.

The piece invites participants to press themselves against a wall, and to consider the effect of doing so has on their body. They are encouraged by Nauman’s words to think about what impact the contact with the wall has on the various parts of their anatomy, and later to explore specific details: “Concentrate on the tensions in the muscles, pain where bones meet, fleshy deformations that occur under pressure; consider body hair, perspiration, odors (smells).” The text ends with a hint about how Nauman anticipates our bodies will react when the work is performed: “This may become a very erotic exercise.”

Nauman’s art is predicated on the notion that an artwork does not always need to be an object, but may be an action or activity, performed either by the artist or by the audience. In this, his work relates to and furthers that of the influential French artist Marcel Duchamp who questioned the meaning of art and introduced the notion of the “readymade”: an artwork created from a pre-existing object, such as his Fountain (1917), a porcelain urinal.

Duchamp’s ideas join with conceptual and performance art in Nauman’s work, and the latter created several videos and photographic series in the 1960s and 1970s in which he is shown performing simple actions. These are usually centered on the body, and on the physical experience. Some—such as Self-Portrait as a Fountain (1966), where Nauman is shown spurting water from his mouth—are simple and witty, whereas others investigate less comfortable experiences, including endurance and claustrophobia.

Body Pressure continues to be an influential performance piece, and formed part of the artist Marina Abramovic’s acclaimed exhibition Seven Easy Pieces (2005) at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, in which she re-created seven seminal piecesof performance art, five by other artists and two of her own works. Nauman’s piece also relates to other explorations of the body by artists in the 1960s and 1970s, including Yves Klein’s Anthropometries (1960), in which Klein painted naked women with his distinctive International Klein Blue paint and made imprints of their bodies on large sheets of paper.

Nauman is also interested in the power and effect of language, and its ability to communicate ideas. He is often playful with words, as can be seen in the text for Body Pressure, in which he emphasizes and repeats the words “very hard,” perhaps with the intention of increasing the eroticism of the piece. How erotic, or not, the experience may be, though, is of course entirely down to the individual participant.

Joan Semmel

Touch

1975

Image courtesy of Joan Semmel and Alexander Gray Associates

The American artist Joan Semmel began painting her erotic figurative works in the early 1970s in response to what she saw as the sexploitation of the porn industry in her native country. For much of the 1960s the artist had been living in Spain, and when she returned to New York early in the following decade, she was shocked at the way the sex industry was using women’s bodies against them. As a proactive member of the feminist art movement, she began adopting the photographic techniques and subject matter used in pornography to create a series of paintings that presented a different narrative from the fetishized one promoted by the porn industry.

Having trained in Abstract Expressionism, Semmel now turned to photo-realism, using that aesthetic’s crystal clarity to offer an alternative reality. Touch is a painting about a woman’s sexual desire, rather than a man’s, and the artist unsettles the traditional gender power structures by placing the woman’s leg over the man’s torso. But it is the unusual perspective of the picture that creates the intimacy. Although the figures are headless, they are anything but anonymous. In the heightened color, vivid brushstrokes and unusual composition, Semmel reveals the tactile nature of flesh. This is a painting about emotional and physical human contact.

The artist’s gaze is merged with that of the viewer, so that both are looking down on the artist’s naked body and that of her lover’s from the head of the bed. The realistic style and extreme foreshortening, together with the warm amber tones of the skin, add to the sense of closeness. Semmel makes the viewer a participant in an intensely quiet and private moment between two people.